So, I’m doing a thing.

When I set out to try to plan this venture, initially, a few years ago, I thought I was completely different from my parents. We’ll come back to that.

I guess the idea for this whole thing started at my mother’s velorio — her wake, basically. We buried her in Chinchero, Cusco, Peru, where she spent most of her child-rearing years, and we sat up all night with her casket, people dropping by and sharing remembrances, and as the night went on, one question came up again and again: whatever happened to all those notes she and my dad used to take doing anthropological field work? All those stories, all those photos, whatever did happen to them? Now that both my parents were gone, and my sister, what would become of that chronicle, that archive?

If they could be found, I said, then somehow, soon, I would do something with them. And we did find them. Or a large part of them. And in the very beginning, I did a decent job of sorting them, storing them, scanning some of them.

“You know what I should do?” I asked my husband Chad, not waiting for his answer. “I should write a book, where I start the chapter with one parent’s journal or letter or whatever, and then I tell my memory of it along with a retrospective thing that puts it in the larger context, and then close that chapter with a thing from the other parent.”

Chad laughed. “That sounds like about the most Franquemont thing I could picture doing with all of this.” I laughed too, as strange as it might have seemed to laugh, sitting on the floor, surrounded by stacks of folders and papers and negatives and slides and tiny notebooks that fit in a pocket, suitable for field notes with one of the 4-color pens my father was never without.

I wrote some outlines. I tentatively tried to pitch the book, but it was scary, you know? Maybe I didn’t try as hard as I should have. Maybe I thought, hell, nobody wants to read a retrospective by some middle-aged kid going through her dead parents’ stuff. And then life threw some curve balls — ovarian cancer for me, a heart attack for Chad, the decision to develop an electric spinning wheel as a product, that sort of thing. Bit by bit, the project got tabled. I stopped sorting files, stopped pulling out raw field notes about productive rates of spinners in 1977, stopped scanning childhood homeschool assignments to write about learning to weave and spin.

“This is all so tangled,” I said, one day. “I think, once upon a time, I thought I could separate out the stuff that would be memoir and the stuff that was about spinning and weaving; the stuff that would be travel writing, ethnography, and that sort of thing, from the stuff that was about the finer points of technique in being productive with a spindle. But I can’t. It’s just like my whole life. It’s all too intertwined. I can’t take the yarn out of the Franquemont and I can’t take the Franquemont out of the yarn.”

“Then maybe you don’t,” Chad said. “Maybe that’s the whole thing. Maybe it’s not tangled. Maybe it’s a textile.”

Maybe.

(Don’t worry. There’s plenty of yarn talk to come.)

Well, time passes. Mercilessly, in fact. And here it is, 2018, and it came to be November — the 5th anniversary of my mother’s death, and there I was, still no closer, really, to having Done Something with that archive. So I resolved that this year, we’d all go to Peru for Christmas, and I’d come up with a real plan.

The thing is… there was no plan that would allow for me, Chad, and our grownup offspring to go to Peru for very long, without everything falling apart in the USA. And so, dejectedly, I tabled the project again.

And then… one day, Chad told me they’d talked. And that they’d done the math. And looked at the schedule and the hard requirements. And… well, the thing was just this: if we didn’t do the Christmas trip, if Chad and our kid stayed home and sent me off alone, it looked like there’d be a way to send me for about 3 months. Long enough to take my outlines, my notes, and scans of my parents’ archive, and be where I needed to be to do all the research to write the book right. Where I could go follow in my parents’ footsteps.

“Yeah,” said my kid, “And you know, the funny thing is, you could have better internet there than we’ve got here in semi rural Ohio.”

“That’s true,” said Chad. “You could finally do all the livestreams and video lessons you’ve been wanting to and that our crappy net doesn’t allow.”

After much discussion, I ended up saying: “The only way it could work would be if I went, and once there, sorted out a whole bunch of stuff, and we just… totally did it all on a wing and a prayer. It’s crazy. Completely crazy.”

But then I started thinking about it seriously, which Chad would tell you is a uniquely Franquemont thing to do: look at a seeming impossibility, and then start to break it down and find some angle of attack that makes it… not unviable.

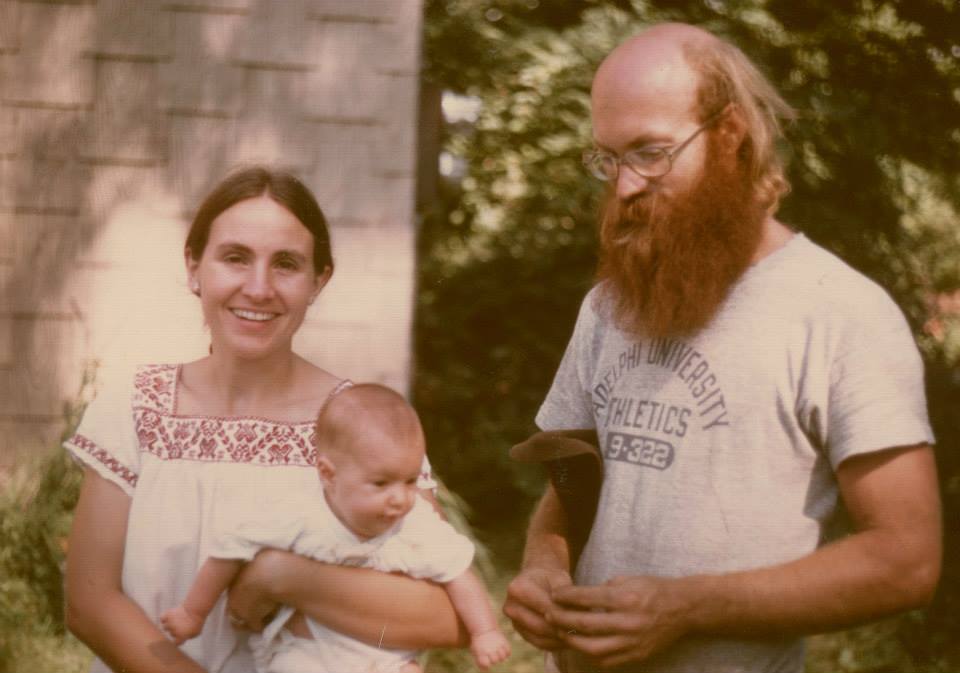

The decision was made, finally, when I sat with the tiny spiral bound notebook my father started on December 28, 1976: a chronicle of the time when, after seeking funding for 6 years and not finding it, my parents sold off everything they owned, took the cash, and moved to Peru with their 4-year-old (me) and 1-year-old (my sister), with no clear plan for how they’d use their bottom dollar to pull off the textile research project they’d proposed over and over again, only to hear a million reasons why it couldn’t work, was ridiculous, and nobody was interested.

If I were to go now, I could work on that book project — and I could blog the process. And it’s 2018. Now there’s internet everywhere. Now the electricity in Peru can be taken for granted. Everybody’s got flushing toilets. You can even have an ice cold beer that’s been refrigerated. What obstacles did I really face, as compared to my parents?

We went through the lists, and crossed them off, or set them to the side, and then ultimately, the biggest one was: how the hell do we explain this to all of our friends and customers and students and everyone?

Well, I guess we do it like this.

(Come on you guys, be serious, I’m trying to take a serious selfie here dammit)

Expect to hear lots more in the next few days, about how you can follow along, what exciting new things you could potentially take advantage of (like an online spinning lesson or scheduled livestreams about spinning and weaving, just for starters). There’s also great news from the Questionable Origin e-spinner side of things, and I’ll leave that for Chad to announce, and it will probably be much shorter, sweeter, and to the point than I ever seem to be. But for now… It’s Christmas in Cusco, the capital of the empire whose heirs claimed me to educate as a proper weaver and spinner.

(You bet she’s spinning.)

More tomorrow.