Dear Chris,

Well, it doesn’t get any easier.

Today, you would be 70.

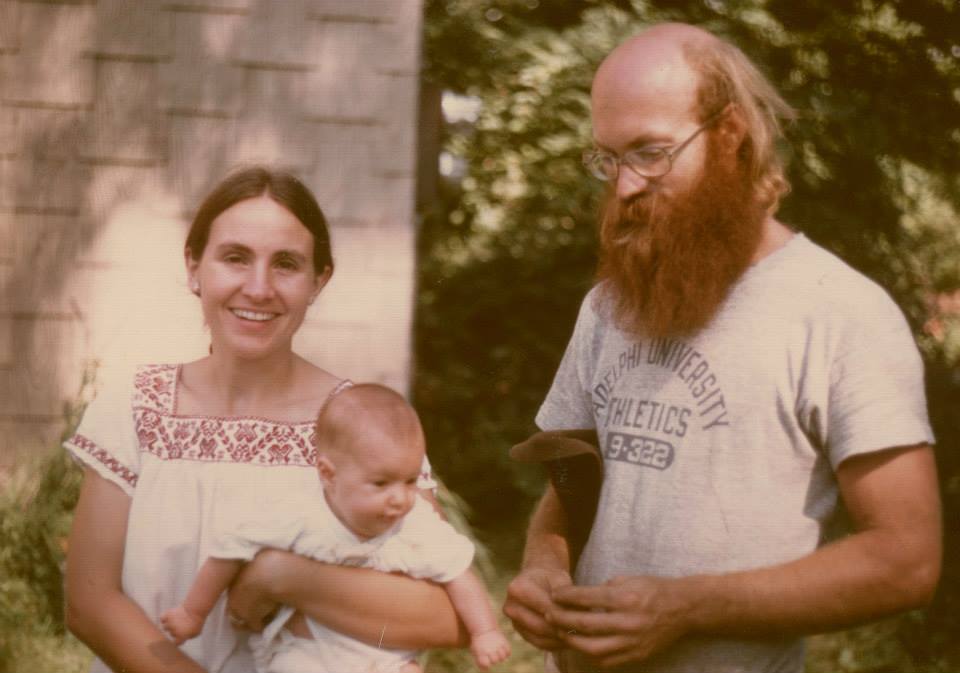

Five years ago today was the last time I wished you a happy birthday, and the last time anybody heard from Molly.

I spend a lot of March 9ths bursting into tears suddenly, and today’s really no exception. And yeah, to be fair, it’s been a rough day ever since that birthday of yours when we all rushed to Ed’s deathbed and made you leave for long enough to go have a good solid meal. It was your 56th birthday — you were only ten years older than I am now. And we never could have guessed you only had 9 more birthdays coming.

Do you remember that nightmare I used to have, over and over? I know, there were a few. But I mean that one where one day, you and Ed decided we should get a refrigerator for the cancha at the house we lived in, Mateo Pumaccahua’s house, and then we could all have milk and maybe even ice cream, in Chinchero just like we used to on the farm in Bolton?

So, yeah, anyway, we set off (in the dream) over to the other side of Antaquilka — which by the way, you still can’t actually find notated on maps very easily. And yeah, he’s still my apu, but I guess you know that since he’s watching over your bones real close. But yeah. I was shocked, in the dream, when the other side was all pink and white stripes. Bare shale type rock in so many places, all pink and white. I’d never been there, and in real life I assumed his other side was green and steep and imposing the same way the face of him I saw daily was. But no. Pink and white shale stripes.

And down into the dream valley we walked. Well, you and Ed and I walked, and Ed had Molly on his back in a k’eparina. He stepped careful, on the downward slope, with his bad knees and his feet in wool socks inside some old ojotas. I ran with a five-year-old’s glee, down and back up and down again, tireless, faster than all of you, and I was the first one there to the odds and ends ferreteria where rumor had it there was a fridge.

Ed put Molly down, in her pink balleta culis, to run around and maybe find somewhere to go pee. I wandered after her, like the good big sister I strove to be. But then Ed called me back, to take a look at the fridge. I took Molly’s hand and made her come, too, and then you picked her up and held her on your hip while I walked around the fridge, inspecting it from all sides.

“What do you think?” Ed asked.

I took it all so seriously. Just like you told my kid, that time when he asked you what his mother was like as a little kid. “She was very serious,” you said. “She never did anything she wasn’t serious about doing.” So in the dream, I checked out that fridge like lives depended on it. I mean, they would, if we got it, and got it back up to Chinchero, and if we got to the pasteurizing milk and keeping it and then maybe even making ice cream sometimes. So many reasons you both had explained to me, about why we didn’t have milk and didn’t have ice cream and why I wasn’t supposed to just eat choclo con queso without knowing about the source of the cheese. And I thought about all these things, very seriously, in my five-year-old dream way.

“Yes,” I said. “Yes, this should do the trick.”

I turned around to confirm you’d all heard me, but Molly was back in the k’eparina on Ed’s back, and the three of you were headed down the road, down the valley, down along the riverside.

“Stop!” I yelled, “Wait!” as I started to run after you. I mean, I was sure I could catch you. I was fast. So fast. And you guys would wait up.

Except you didn’t. You just looked back, and kept going. And then you laughed. You all laughed. And no matter how fast I ran I couldn’t catch you, and then laughing, the three of you disappeared around a bend and there was nothing for me but to sit by the side of the road, sobbing, sweaty, dusty, between a cactus and a rain-melted adobe wall atop an Inca foundation.

In hindsight now, sometimes I think that recurring dream was Antaquilka trying to tell me how it would be — that I would be there, taking it all so seriously, and then somehow you’d all three of you be gone, and I wouldn’t be able to catch up, and I’d be in the dust looking at an unripe tuna fruit and a much older Molly saying “no, Opuntia,” and poky needles and legless white beetles we all know hold bright red inside, the fine powdery dust of the Andes in my nose, what used to be someone’s house but now it’s all melted from rainy season after rainy season, pillaged tombs up on the steep cliff behind me, bright yellow-flowered retama shrubs, the smell of that invader eucalyptus and its blade-like leaves, the rushing river not so distant, and all of you gone around the bend and I can’t catch up.

Sometimes I wish I hadn’t learned to know it was a dream, or that I hadn’t learned to wake myself from it and know it wasn’t real. Maybe then I would know what happens next. Or how many more bends the road still holds. Or if there’ll ever be ice cream where once there was none. Hell, if anybody bought that fridge, or if I ever made it home.

On Sunday, it’ll be 14 years since I put that bag of Fritos in my father’s cold, dead hands, and said I wished I had a beer for him, and then you said I should take the scarf I had crocheted for him, and I said it was his, and you said it wasn’t like we did grave goods in Connecticut. I’m glad you didn’t die in Connecticut. I’m glad that’s not where your bones lie. Fuck Connecticut. For me it’s still another word for death and despair. Maybe if it had gotten to stay quinetucket, “beside the long tidal river,” it would mean that less. Maybe not. Maybe it’s just me. I mean, it is just me, I suppose. And the apu tried to tell me. I should have prepared better. But here we are. Or aren’t.

I guess, again, I’ll leave you with this song that Ed used to sing — that we all sang.

I love you, and I miss you, and I hope you are all three of you together, held close by the apus and the rivers and whatever it is that ties it all together. That somewhere, some mountain and some river hold Molly’s long-lost bones, that it’s not the ñakaq who took her, and that you all can laugh, leaving me behind, and know I’ll be okay. And I try so hard to not just be a little girl lost by the side of the road. But some days it’s just so hard, and all I can do is cry.

Here’s to you, my ramblin’ fam — may all your ramblin’ bring you joy.